Nov

06

Posted by Liz Morris on November 6th, 2024

Posted in: Blog

One of the most heartbreaking stories you can tell an archivist or librarian is when a collection of recorded knowledge is lost forever. However, some of the most fulfilling stories are when dedicated individuals piece together a history that everyone assumed was lost. For this blog post, I am honored to share both heartbreak and fulfillment with you as I tell the story of the University of Washington Gender Identity Clinic’s lost records and the dedicated work of Os Keyes.

A History Assumed to Be Lost Forever

The University of Washington Gender Identity Clinic provided sex reassignment surgery from 1967-1972, with a primary focus of male-to-female procedures. This clinic was the third gender identity clinic documented within the United States and the first gender identity clinic on the west coast.

Led by Dr. John Hampson, a committee comprised of anthropologists, psychiatrists, sociologists, and surgeons selected candidates through an initial screening and intensive interview process. Through grant funding, the program covered the surgical costs involved. The deposit payment made by patients would be paid back incrementally as they participated in follow-up interviews.

After the main surgeon, Dr. J. William (Bill) McRoberts, relocated in 1972, the clinic dissolved; however, small procedures were provided ad-hoc up into the 1980s. The extensive records held about the clinic were unfortunately lost when the Tubbs wildfire in 2014 hit the home of a researcher who held the records for a future follow-up with patients on the long-term outcomes of their gender-affirming surgeries. For about a decade afterward, no comprehensive record existed documenting the work of the clinic and the people involved.

Reconstructing the Memory of the Clinic

Os Keyes, postdoctoral researcher, noticed the lack of available record on the clinic while working on their dissertation research. They conducted interviews with individuals involved with the clinic, including clinical staff and one patient, to learn more about the program and where the records went. Once they learned that the records were accidently lost in a fire, they dedicated numerous hours sorting through public records and archival collections to reconstruct the remaining documentation around the clinic and its patients.

For more information on Keyes’ methodology, they recently published an article in Logic(s) describing their process.

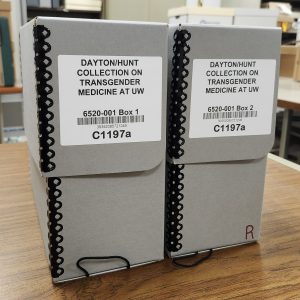

Photo of University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, Acc. No. 6520-001

Preserving the Reconstructed History

For my Master of Library and Information Science Capstone project, I worked closely with Keyes and the University of Washington Libraries Special Collections to accession and process the reconstructed records of the clinic.

This project was unique to other archival collections that I have worked with previously because it required continual collaboration with the donor and subject expert. To ensure I provided accurate descriptions and provenances within the ArchivesSpace record and finding aid, Keyes reviewed numerous drafts for the historical note, transcripts, and inventory list. This iterative process best fit our concerns around creating a clear and context-rich finding aid while responsibly redacting or restricting patient-sensitive information.

In total, the physical collection is 2 boxes (0.74 cubic feet), containing human resource files, publications, court documents, correspondence, and interview transcripts. Digital materials include audio recordings from interviews, photo reproductions of related teaching slides, and film reproductions. The organization of the collection allows for the general public to access one box containing non-sensitive or otherwise redacted records. To access the restricted box, researchers will need IRB and donor approval.

Personally, I find the interviews between Keyes and relevant individuals to be one of the most compelling parts of the collection. These interviews provide a retrospective view of the clinic and the experiences of various staff and one patient. I transcribed each interview and created redacted versions for increased user access.

The collection, “Dayton/Hunt Collection on Transgender Medicine at the University of Washington” (Acc. No. 6520-001), is now available for patron viewing. The finding aid can be found on Archives West.

Sharing Out the Collection

While my part in this project has ended, I am continually talking about this collection whenever I can, so people know that these records exist and are available. In May, I presented a poster highlighting the collection for internal UW Special Collections staff. The hope is that now that staff are aware of the collection, they can recommend it as a resource for future patrons. Additionally, I presented on this project at the Washington Medical Librarians Association conference in Ellensburg, WA in July. While most of the attendees do not have an archival focus, I wanted to share the story of this collection with them to promote the use of Special Collections within medical librarianship.

Though the loss of the original clinic records continues to break my heart, I am hopeful that this collection can be one of many to document and preserve transgender medical history.