Jul

21

Posted by nnlmneo on July 21st, 2017

Posted in: Blog

If you read articles about evaluation sooner or later you will read that your evaluation plan needs to have a good Theory of Change (for example, it’s part of “evaluability assessment” that I wrote about on July 7, 2017). This has concerned me because I assumed there were probably a lot of theories of change in the academic world, and I had to be knowledgeable about all of them so I could select the best one for my evaluation project. And there would be the possibility that someone come by later and say “why did you pick the Eisenstein Theory of Change? I would think the Schulenberg Theory would be more appropriate to this project.” I don’t know about you, but to me this was a scary proposition.

Thank goodness Cindy Olney recommended this USAID Learning Lab article to me called “What is this thing called ‘Theory of Change’?” When I read it, it sounded comfortingly familiar.

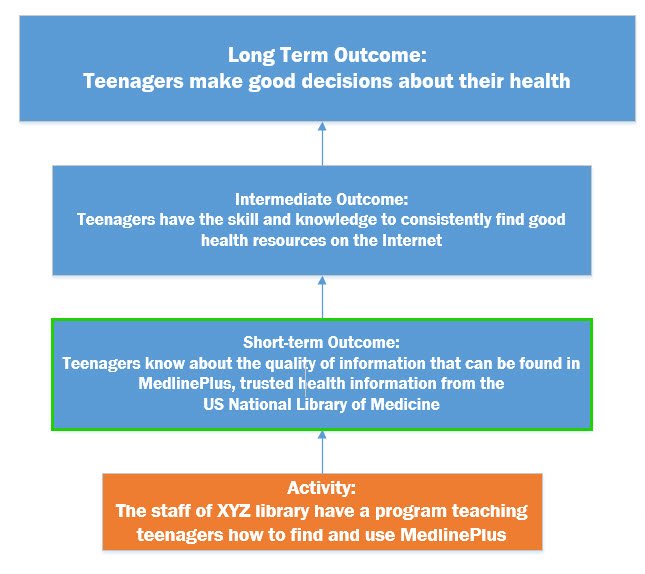

When you are planning an activity (for example, teaching teenagers about MedlinePlus), you have a long term goal (teenagers make good decisions about their health). The Theory of Change (ToC) is how you know that point A (learning about MedlinePlus) will logically get you to point D (teenagers making good health decisions). You would start with the long term goal, and then see what conditions need to be in place to reach that goal.

The logic might look something like this: In order for teenagers to make good health decisions, they need to have access to high quality health information. Because teenagers report using the internet to learn about things that affect their health rather than asking a health professional, in order for them to have access to good health information they would need to consistently find high quality health resources on the internet. Because the internet is full of bad health information, teaching teenagers how to get to the high quality health information found in MedlinePlus will put good information at their fingertips. Voila – we have logically connected point A to point D. And we can show this in a diagram.

The logic might look something like this: In order for teenagers to make good health decisions, they need to have access to high quality health information. Because teenagers report using the internet to learn about things that affect their health rather than asking a health professional, in order for them to have access to good health information they would need to consistently find high quality health resources on the internet. Because the internet is full of bad health information, teaching teenagers how to get to the high quality health information found in MedlinePlus will put good information at their fingertips. Voila – we have logically connected point A to point D. And we can show this in a diagram.

Later on when you are evaluating the results of your activity, if the teenagers who participated in your project reported making better health decisions, your theory of change has to be strong enough for you to confidently say that teaching them about MedlinePlus contributed to their success. As the USAID article says “a ToC is the thinking behind how a particular intervention will bring about results.”

Does this sound familiar to anyone? It’s the process we go through when we start with outcomes and then build a logic model.

What this tells me is that a logic model is more than just a guide to doing a project while staying focused on your outcomes (planning a birthday party, for example). Logic models help show credibility of your evaluation results. If your logic showed that teaching MedlinePlus led to World Peace (I’m not saying it doesn’t – only that the logic might be weak), then you could collect and report all the data you want, but you might have trouble having your evaluation taken seriously.

In addition, the diagram that describes your theory of change is important. It can be any diagram that shows how you are planning to go from your activities to your outcomes. The importance of the diagram is that you can show it to other people who might either agree that it’s logically sound, or who might know about some factors that you haven’t considered (maybe this group of teenagers doesn’t have easy access to the internet). So yes, you might show it to someone who says “there are flaws in your theory of change,” but they won’t be talking about Delancey’s Theory vs. Paterneski’s (I’m having a good time making up sciencey-sounding theory names), but they will be helping you see how you can improve your project to reach your goals and improve your evaluation plan, which are good things.

So, moral: put a lot of thought into your logic model. Show it to your stakeholders (Logic Model Hack: the Project Reality tCheck), and make sure you’re making a sound rationale showing that your project leads to your long term outcomes. Then build your evaluation plan based on a solid logic. And when someone down the road says “what was your theory of change when you planned your evaluation?” you can pick up your logic model and show it to them.